The United States is facing a literacy crisis. Yes, crisis. It isn’t new, but its impacts upon our kids, our economy, and our society are far-reaching and expanding. How bad is it? Take a look at some numbers.

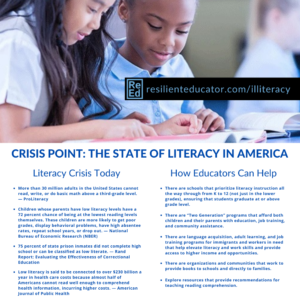

- More than 30 million adults in the United States cannot read, write, or do basic math above a third-grade level. — ProLiteracy

- Children whose parents have low literacy levels have a 72 percent chance of being at the lowest reading levels themselves. These children are more likely to get poor grades, display behavioral problems, have high absentee rates, repeat school years, or drop out. — National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

- 75 percent of state prison inmates did not complete high school or can be classified as low literate. — Rand Report: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

- Low literacy is said to be connected to over $230 billion a year in health care costs because almost half of Americans cannot read well enough to comprehend health information, incurring higher costs. — American Journal of Public Health

The history of American literacy

To truly understand the state of literacy in today’s United States, we need to go back to the beginning. Literacy has long been used as a method of social control and oppression. Throughout much of history, the ability to read was something only privileged, upper-class white men were allowed to learn. School wasn’t free like it is today. Education was provided to only a select few, and this preserved a class system that kept the poor powerless and the rich powerful—a practice, we’ll see later in this piece, that continues today.

According to the Smithsonian, after the slave revolt of 1831, all slave states except Maryland, Kentucky, and Tennessee passed laws that made it illegal to teach slaves to read and write. The Alabama Slave Code of 1833 included this following law: “Any person who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read or write, shall upon conviction thereof by indictment, be fined in a sum of not less than two hundred fifty dollars, nor more than five hundred dollars.” That was a whole lot of money in 1833. Why were they so concerned about slaves learning to read? Because if slaves learned to read, they could access information. They could read newspapers. They could read books and understand their rights. They could organize and rise up against the institution of slavery. Slave owners wanted to keep their slaves uneducated and powerless because they understood that literacy represents power.

A prime example is former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass who learned the alphabet secretly as a child from his slave master’s wife, Sophia Auld. As a young adult, Douglass pursued learning on his own, secretly reading books and newspapers. He famously said that “once you learn to read, you will be forever free.”

Schools + learning to read

In the 17th century, public schools existed in the New England states, but largely taught students about religion and family. It wasn’t until the 19th century that public schools truly focused on academics. In the South, public schools were slower to arrive. Rich people paid private tutors to educate their children in the southern states, relegating the poor to perpetual disenfranchisement. The main author of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, created a bill in early Virginia (in the 1770s), titled “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge.” His bill proposed that public schools should be started in Virginia to teach basic “reading, writing, and common arithmetic” to “all the free children, male and female.”

This did not, however, include slaves. His bill was not passed, nor was any public school law in Virginia until decades later in 1796. The 19th and 20th centuries saw the most growth in education and popular literacy. We then saw steady increases in literacy rates until the 1980s—when rates began to dip slightly.

Female literacy

Women, too, were largely left out of education. Educating women simply was not a priority until the early 1900s and even then, women attending college was rare up until the 1960s. Early Americans often believed it was a waste to educate women past the basics since they would need to run a home and raise a family. Bard College’s Joel Perlmann and Boston College’s Dennis Shirley say that “half the women born around 1730 were illiterate.” Women might have been taught to read at home or in an early girls’ school, but they largely weren’t taught to write, and often didn’t have access to secondary school in the early American colonies and states.

Literacy as a social justice issue

Think about it: When someone cannot read, they are excluded from many of the things that allow us to be fully functional citizens with choices. Those who are illiterate can lack access to information, are excluded from making choices about their rights or government through voting, and have fewer opportunities for employment. Illiteracy keeps people trapped in a cycle of poverty and subjugation, limiting life choices and making it difficult to achieve social mobility. Literacy truly is power—power over one’s own life.

While today’s American public schools are compulsory and free to attend, and we now have things like television and the internet, reading still remains a critical pathway to freedom.

The achievement gap

In the United States, literacy rates vary greatly between racial and socio-economic groups. Even today, minorities are still oppressed by lower literacy levels. Literacy continues to be a mechanism of social control and oppression. On the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress 12th Grade Reading Level Assessment (2015), 46 percent of white students scored at or above proficient. Just 17 percent of black students and 25 percent of Latino students scored proficient. Females scored higher than males. In McKinsey & Company’s The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America’s Schools, “Black and Latino students are roughly two to three years of learning behind White students of the same age.” McKinsey’s research showed that that the achievement gap can lead to “heavy and often tragic consequences, via lower earnings, poorer health and higher rates of incarceration.” This achievement gap becomes an opportunity gap, an economic gap, and a racial gap, which gets passed on generation to generation unless it’s disrupted.

The literacy crisis today

Comprehensive national literacy studies are not conducted annually, but the National Commission on Adult Literacy released its report in June 2008 naming several factors contributing to the nation’s literacy crisis. Minority and immigrant groups are growing in population, but remain low in educational achievement.

The report claims that 1 in 3 people in the U.S. drop out of high school and that 1 in 4 American families is low-income with parents who lack education and skills to improve their economic status. This maintains a cycle of poverty, affecting each new generation of children.

In addition, 1 in every 100 adults is in prison in the United States, and more than half of those inmates have low literacy skills. Lastly, language barriers resulting from increased immigration have contributed to lower literacy levels in modern America. According to the Center for Immigration Studies, 41 percent of adult immigrants score at or below the lowest level of English literacy and 28 percent have not completed high school, limiting access to higher education, employment and increasing the likelihood of living in poverty.

What other studies are finding about literacy

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics released the results from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The PIACC provided an overview of proficiency in adult literacy, numeracy and problem-solving. In literacy, people born after 1980 in the U.S. scored lower than 15 of the 22 participating countries. Overall, U.S. adults aged 15-65 scored below the international average in all three categories— ranking near the very bottom in numeracy.

Other studies by testing agencies and literacy organizations confirm the widening literacy gap, the perpetuation of poverty and a resultant expanding unskilled workforce in the coming years—the economic, social, and health-related results of which could be dreadful for the United States as a developed nation. The NCAL report notes that the U.S. is less educated than it was a generation ago, and our growing levels of illiteracy will foster a downward slide in our ability to compete economically with other nations. McKinsey Research finds that education gaps have contributed more than recessions to trillions in GDP losses. Not to mention, a national abjection from the unending toxicity of racial divides built upon 300 years of oppression and antipathy.

Today we see these divides widening, and the impact will be immense as poverty, racism and achievement gaps continue to pass down to future generations. United Nations Special Rapporteur Mutuma Ruteere called poverty and racism “inextricably linked,” noting that “racial or ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by poverty, and the lack of education, adequate housing, and health care transmits poverty from generation to generation and perpetuates racial prejudices and stereotypes in their regard.”

What we can do as educators

Literacy is an authentic and complex social justice issue as it determines many of the factors that contribute to a student’s future quality of life. As teachers across the U.S. will tell you, especially those in low-income areas, students are coming to their classrooms each year reading well below grade level.

There isn’t one magic solution to our nation’s literacy problem—mostly because its causes aren’t singular. However, good work is being done in communities across the country that we can learn from:

- There are schools that prioritize literacy instruction all the way through from K to 12 (not just in the lower grades), ensuring that students graduate at or above grade level.

- There are “Two Generation” programs that afford both children and their parents with education, job training, and community assistance.

- There are language acquisition, adult learning, and job training programs for immigrants and workers in need that help elevate literacy and work skills and provide access to higher income and opportunities.

- There are organizations and communities that work to provide books to schools and directly to families.

It’s these holistic approaches that address not only reading at the classroom level for students, but that acknowledge the contributing factors to illiteracy and achievement disparities.

The work we do every day as teachers is part of the solution to this crisis. The bottom line… keep working, educators. And the more multigenerational programs we can offer, and the most literacy instruction we provide throughout a child’s progression through school, the better the outcomes for our students, our communities, and our nation.

Categorized as: Current Events

Tagged as: Adolescent Literacy, Language Arts, Literacy, Reading Interventionist